The showdown between "Super Mario" Ziad vs. Ostaz Faour: memories from a childhood in Lebanon

In honor of Father’s Day (Sunday, June 21), we’re sharing a memory written by an UNRWA alum, father, and semi-retired trouble-maker, Ziad Ismail.

While we’ll let Ziad give his own introduction, you may recognize his name as the inspiration behind the iconic NYC Gaza 5K team ‘hi guys.’ Ziad, affectionately referred to as ‘ammo Ziad (or Uncle Ziad), grew up in various refugee camps in Lebanon. To this day, he is known for his love for the phrase ‘hi guys’ and his iconic mustache, which his children will now claim has always been there, even as a child. This ‘stache is so iconic, in fact, in the stories of his childhood, he is described by his family as a young, Palestinian version of “Super Mario, hopping off the stacks of cinder-block buildings of Burj al Barajneh camp and banging on corrugated tin roofs with a tightly wrapped sandwich in his left fist and a stick in his right.”

Though mischievous as a kid (and perhaps still to this day!), his story represents not only the way that refugee kids are playful, smart, and curious, like kids around the world, but also the way in which the UNRWA community of teachers, principals, and employees, provides a secondary source of parental guidance to refugee kids. These role models and community leaders emphasized the strong communal values that Ziad and many other Palestine refugees now impart on their own children.

Ziad, mustache and all, is pictured below alongside his wife and kids

ziad’s story

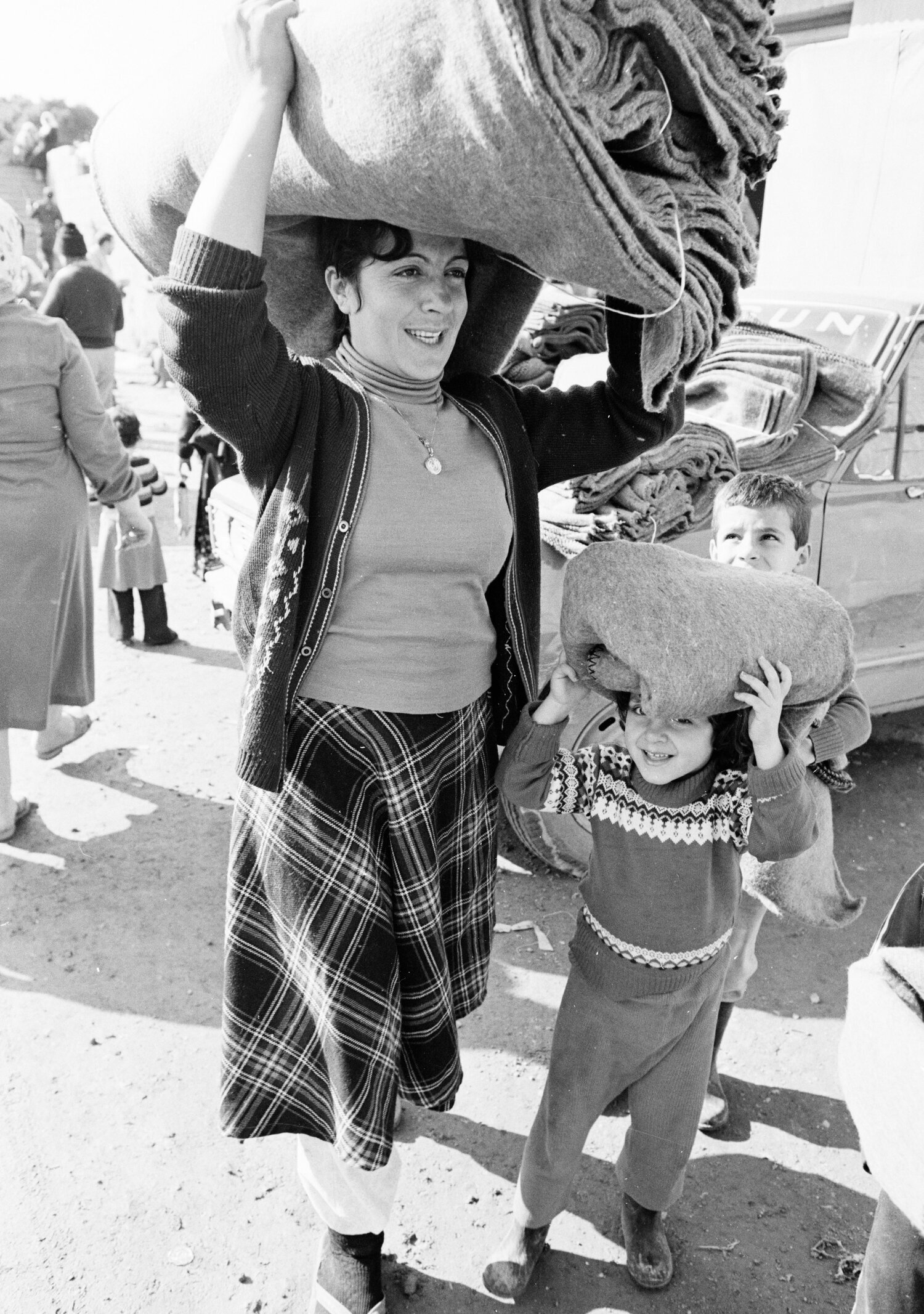

Young Ziad, age 6, pictured in his UNRWA school uniform. Notably, this the only photo he has from his childhood. We can’t say for certain, but we’d like to think he’s wearing two sets of pants and has a handkerchief in his pocket (read Ziad’s full story to get the reference).

My life began like any other, in that I was born.

I was born differently, though, than my siblings before me, and my parents and grandparents before them, in that my very coming to life, the very act of opening my eyes, my heart’s first pump, the wails echoing out in Burj al Barajneh that day in April 1950 were powered by a breath of different air coursing its way through my tiny little lungs – the air of exile.

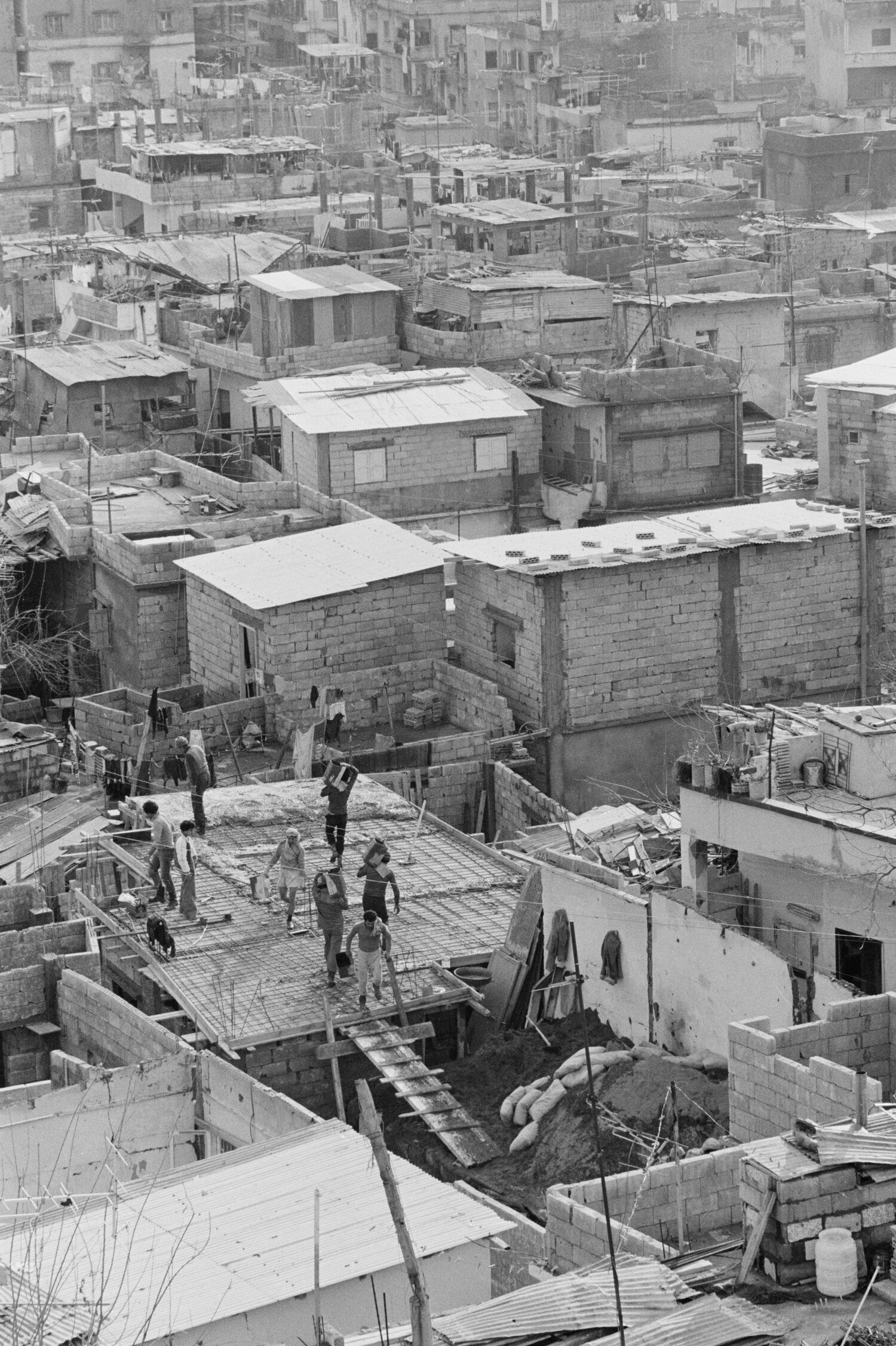

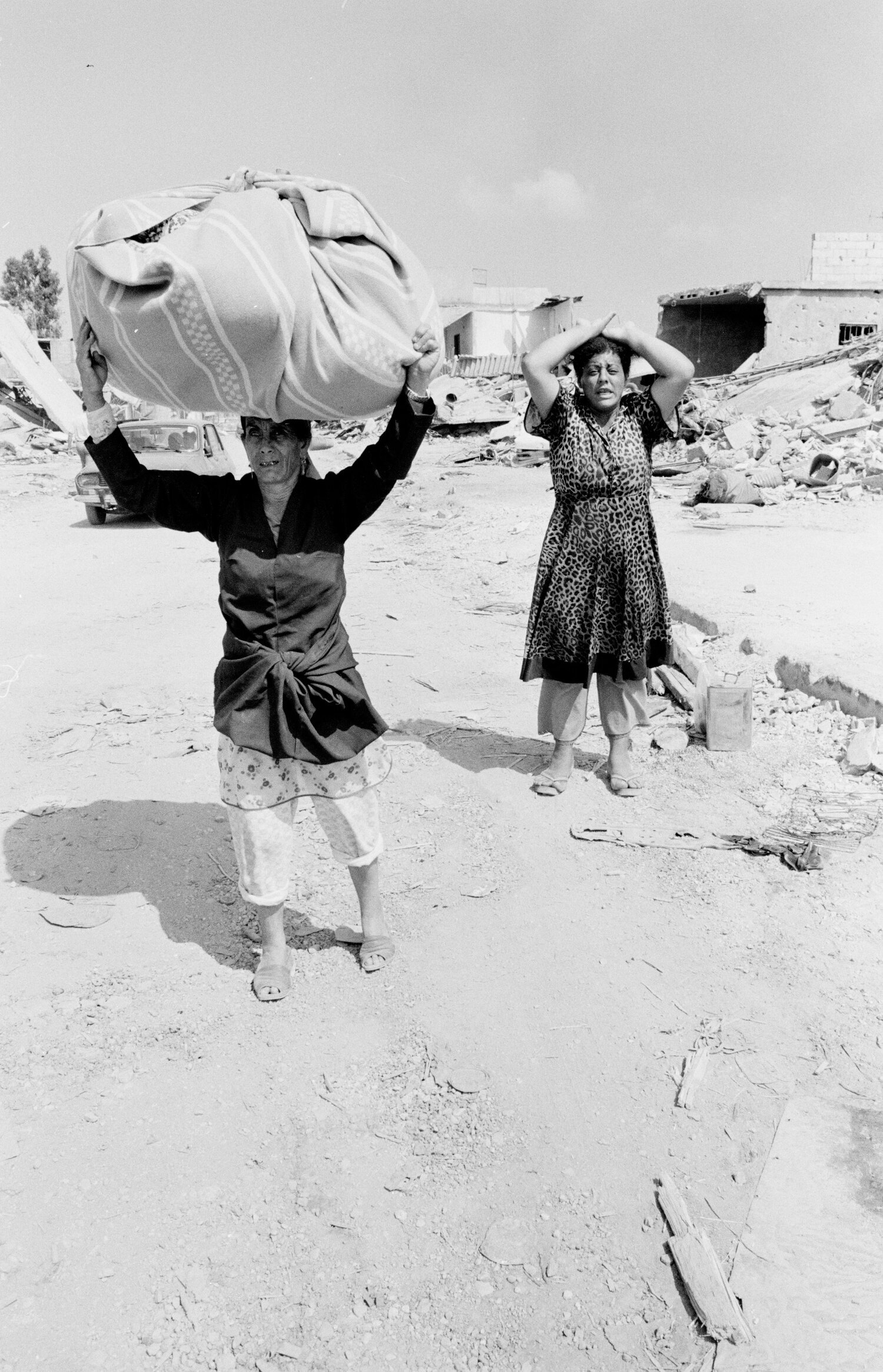

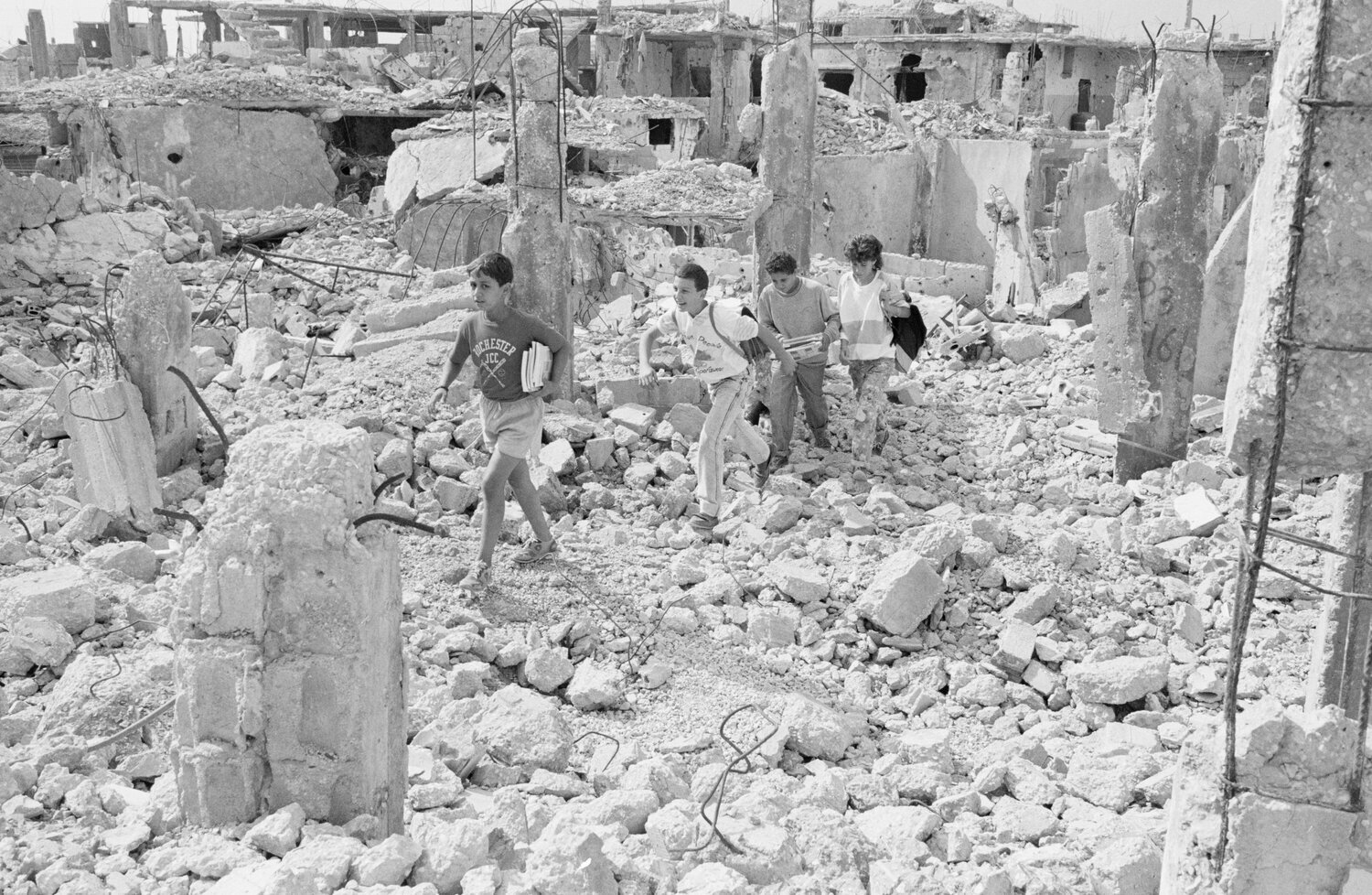

I took my first breath and first steps 70 miles from where everyone else in my family had taken theirs — a home I’ve never stepped foot in and have only heard descriptions of in Sha’ab, in Palestine. Instead, the homes I grew up knowing were in Burj al Barajneh, Shatila, and Sabra in Beirut. The schools I knew were in those refugee camps too. When we call them camps, maybe you think of tents and temporariness. But as much as we grew to hope they would not be our forever homes – each morning in school we sang an ode to Palestine and gestured southward toward our homeland – we lived in them as if they were.

School was the cornerstone of my childhood, and our UNRWA teachers became legendary in a matter of years. Some, like our principal Mohamed Faour, picked up right where they had left off in Palestine, building on reputations as stern, uncompromising teachers; others like my brother Adel learned quickly and began a life of teaching which continues to today. And while we often yearned for the normalcy of going to a regular school like Lebanese kids, we eventually learned that our education – an education by our people, for our people, often about our people – was incomparable. Our teachers were committed to us – they were counting on us to be something, to mature into people they could be proud of. They taught us math, science, English, and Arabic, but they also checked under our fingernails for dirt every morning and made sure we had a handkerchief in our pockets at all times, so we didn’t wipe our noses on our sleeves. One time, I forgot mine and pulled my pocket lining out of my pants when the teacher passed by in the morning lineup. I may have forgotten my pocket lining, but you better believe I remembered to wear two pairs of pants for extra padding. Ostaz Faour (“ostaz” or “teacher” in Arabic) was a disciplinarian, and he made no bones about it.

UNRWA archive images of refugee camps in Lebanon

One year, as summer approached, we were preparing for national exams. Our teachers took these exams seriously – many of them told us that our fate as a people rested on how Palestinians from UNRWA schools fared on Lebanese national exams. The teachers came in an extra day as exams approached, and we were of course expected to do the same. Not all of us were on the same page, though. The weather was nice, the school year was ending, and we all wanted to go to the beach to play football. All of us, that is, except for one goody-two-shoes who always had clean fingernails, always had a handkerchief, and only ever wore one pair of pants. When our teacher got to school Friday morning, he found the goody-two-shoes sitting in the front row, desperately waiting to share what he knew. Where are your classmates? Ostaz Faour asked. The goody-two-shoes grinned and told him we had decided to shame all of Palestine by playing football on the beach.

“Our teachers were committed to us – they were counting on us to be something, to mature into people they could be proud of. They taught us math, science, English, and Arabic, but they also checked under our fingernails for dirt every morning and made sure we had a handkerchief in our pockets at all times, so we didn’t wipe our noses on our sleeves.”

At this point, it’s important to tell you that Ostaz Faour was cool – so cool, in fact, that he had a motorcycle. And the goody-two-shoes knew it. Ostaz Faour jumped on his motorcycle and told the goody-two-shoes to hop on back. He did, grinning the whole way to the coast, where we saw them zooming toward us as we strung passes together across the sand. We knew it was Ostaz Faour from the determination with which he hit the brakes as he arrived.

We were caught.

He jumped off of the motorcycle, barely saying a word to us. He looked at the goody-two-shoes. Open the basket. Hand me the rope, please, goody-two-shoes. He finally connected eyes with us. You. Will. Pass. Your. Exams. He tied the rope to the back of his motorcycle. For. Yourselves. He began to wrap it around us all, a classroom full of 12-year-olds. And. If. Not. For. Yourselves. For. Your. Parents. He brought the rope back to the motorcycle. And. If. Not. For. Your. Parents. For. Your. People. Ostaz Faour took mercy on us. He revved slowly, and let us jog most of the way back, with the occasional sprint here and there to keep us on, shaming us mostly with goody-two-shoes looking backward at us as we made our way back to school. As always, I wore two pairs of pants that day, which I was grateful for when I bumped against the ground here and there.

Do you have an ‘ammo Ziad in your life whose stories make you both laugh and cry?

A father figure, whether that be a ‘baba,’ uncle, step-father, brother, or godfather who has been with you to share laughter, tears, memories, and has always pushed you to be the best version of you? You can honor him this Father’s Day with a monthly gift in his honor that sustains UNRWA USA’s work and provides year-round life-enhancing health, education, and protection for Palestine refugees.

Give before Father's Day (June 21, 2020) and we'll send your #1 guy a special-edition, colorful Gaza keffiyeh from the Hirbawi Textile Factory -- the last remaining keffiyeh factory in Palestine. Your hero will get to rock his keffiyeh in solidarity this Father's Day and forever, knowing he taught you well and that their legacy lives on through you.